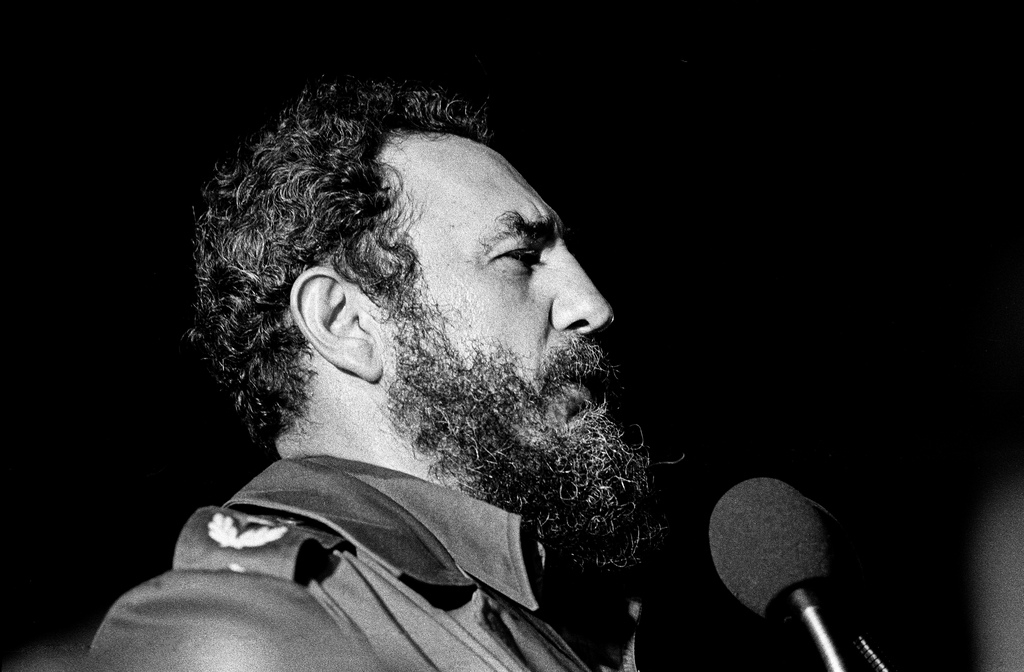

In November 2014 a group of academics met at Pitt to consider the prospects for reform in Cuba from a comparative perspective. Just one month later Cuba and the United states announced their diplomatic opening. That was a dramatic change for the context of reform. Now as we are about to complete our book Reforming Communism: Cuba in Comparative Perspective (forthcoming, Pittsburgh University Press; available at http://www.pitt.edu/~smorgens/) , Fidel Castro’s death could alter that context again. Fidel stepped away from power in 2006 (and formally ceded power in 2008), but his presence, at least symbolic, has continued to hold sway. Several of our authors emphasized that while reform is needed and desired, there are still serious concerns with maintaining the legacies of the revolution that Fidel embodied. His death, then, will perhaps give an extra impetus to reform. At the same time, the election of Donald Trump adds another unknown to the equation. Will he push for more opening to allow more business ventures on the island, or bow to old anti-Fidelistas who opposed any moves to change the US-Cuban relationship?

Cuba faces tremendous challenges, but also opportunities. Its people are restless given the decades of poor economic performance, even if its education and health systems are the best in Latin America. Similarly, it touts is social diversity and gains for women Afro-Cubans after the revolution, but progress on these other issues, from domestic violence to civil liberties have been, at best, limited. Politically, the Communist party has not changed much since its formation several years after the revolution, with the leadership maintaining its centralized and extensive control of society and the economy.

A whispering campaign in Cuba, and a louder discussion from the outside, has expected bigger changes with the death of Fidel. While Fidel’s successor/brother has seemed to be more inclined to pragmatism, critics have emphasized the tepid pace of reforms. A comical, but telling example is noted by Mesa Lago and Perez Lopez in their book Cuba under Raul Castro: Assessing the Reforms (Lynne Riener, 2013): new private employment allow citizens to be clowns but not doctors or accountants.

This type of half measure perhaps reflects the inherent tension in the Cuban society which is the result of two different narratives on the island’s history. The positive story emphasizes the gains of the revolution, which took away the privileges of the few to raise up the downtrodden. It gave the populace health care and brought literacy. And the revolution gave the Cubans honor and pride in their success at breaking the bonds of the United States by withstanding an invasionary force, assignation plots, and a decades-long embargo.

There is also support for a darker narrative. It begins with the putting to death of hundreds who were on the wrong side of the revolution. Castro then gained opponents, both domestic and international, when he nationalized businesses to turn his country towards a communist economic model. He gained more opposition when he decided to consolidate and hold power instead holding elections. His foreign policy, which began with his inviting the Soviets to put missiles on the island and later included forays into Angola and Ethiopia, solidified the opposition by the U.S. government. And finally, when the long promised economic successes not only failed to materialize but gave to widespread poverty, even supporters began to whittle away.

These two narratives have generated deep divides between devoted loyalists and bitter critics. At the same time, it seems that these tensions do not simply cleave the population into distinct parts, because it is also reasonable to favor changes to improve the current difficult situation that do not destroy the tangible and intangible successes of the Castro regime. The 2014 opening of US-Cuban relations has exposed this tension, with longtime opponents favoring, for example, the opportunities to travel and send funds to their relatives.

In Reforming Communism our authors attempt to consider these narratives in the context of discussing potential reforms, or what the Cuban leaders prefer to call “updating.” The book considers economic, political, and social changes, using explicit comparisons with how other countries have reformed from authoritarian or communist systems. As the authors explain, some countries, such as Taiwan and China have had much success in their reforms. But success is not inevitable. Initial conditions create a context and define potential, and the actual policies that a country implements are decisive. In some cases, such as Vietnam, initial half-measures were unsuccessful, but led to further changes. Eastern Europe confirms these lessons, showing how countries with similar backgrounds can move in different directions.

In sum, Cuba has opportunities for change, and Fidel’s death will certainly raise the hopes not only of the regime’s loudest opponents, but also of those who simply hope for rising incomes, civil freedoms, and government openness. Some of the challenges are evident from the comparative context, but others are particular to Cuba and Fidel’s complex legacy. Overall, the challenge for Cuba, without Fidel, is to build on his early promises, rather than the realities of the current socio-economic system. Maintaining the legacy while at the same time “updating” the system, however, may stand in strong opposition to one another.